- Home

- C. P. Dunphey

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002 Page 5

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002 Read online

Page 5

Then he heard the clicking of its nails and he saw the animal crouched in the corner of Kathy’s bedroom, licking at its sores. “It’ll never last,” the dog said.

The dog was proven right a week later. Kathy sent Clay a text saying that she was getting back together with her ex; that Clay was a nice guy but that he needed to work on his issues. Clay called Kathy and said some harsh things in reply. He called back five minutes later with intent to apologize, but by then she’d already blocked his number.

When Clay got back to his house, the black dog was waiting for him on the stoop with a beaming canine smile, as fat and sleek as it had ever been. The dog leapt onto him just as he began to cry and licked the tears from his cheeks with its slimy, sandpaper tongue.

“Your mistake was letting that dirty bastard Hope get a shot at you,” the dog said. “Hope is just the herald and harbinger of despair. Nothing more. But it’s all right, buddy, you’ve always got me.” Clay threw his arms around the creature’s neck and wept freely. After that he never doubted the dog again.

Clay fell into a melancholy stupor that made his previous ruts look like triumphs by comparison. On many days, he didn’t have the energy to do anything but lie in bed, chain-smoke, and stare up at the cryptic marks he’d drawn on his ceiling, while his dog nuzzled up close under his arm and whispered imprecations into his ear. Eventually he was fired from his job, and then he barely had to leave the house at all. His unemployment swelled the black dog to the size of a Great Dane.

Squalor reclaimed all the places that Clay had cleaned, and salted the Earth. Columns of ants infested his kitchen counters and trash-strewn rooms, and flies buzzed thick in the air. Clay took to carrying a can of aerosol poison. When insects crawled on his bare skin, he sprayed them with death, but like a callous World War I general, the ant queen kept sending wave after wave of her soldiers to die pointlessly in the gas. The poison added a new tang to the already-overpowering miasma. Clay’s skin erupted in furious red rashes, and the chemical stench gave him a headache that never went away, but he figured that he could bear those symptoms better than he could bear the bugs climbing all over him.

One day, Clay was curled up on the floor stroking his dog’s fur and quietly weeping when he felt tell-tale tickles on the hairs of his calf. He sprayed his leg with poison, and then brushed the tiny corpses away. Moments later, however, the ants started moving again. He gave them another long blast of the gas, until the ground beneath them was damp, but they continued to march. Clay swatted them with his palm, crushing them . . . and yet they did not stop. Another ant came over to investigate. One of her smashed sisters bit her head off.

Clay got to his feet—no little undertaking, given his girth—and pushed back his couch with a strained gasp to reveal the cockroaches that he knew lived beneath it. He crushed one of the vermin beneath his bare heel with an audible crunch, pressing its entrails into a carpet already so dirty that a deposit of roach guts barely made a difference anymore. The insect did not stop wiggling. Its top half crawled in one direction still dangling its insides behind it, and the bottom went the opposite way.

From that point on Clay’s house was a zombie apocalypse-writ miniature. The dead hunted the living without mercy, seeking them out in the innumerable nooks and crannies of Clay’s heaped garbage. Dead flies fluttered in the light fixtures until they burned to immobile cinders. Dead ants staggered back into their burrows to slaughter the queens who had birthed them. The insecticide stopped having any effect at all. Clay’s only option was to crush the bugs when they crawled onto him, and even when he did so their limbs continued to squirm. Eventually he stopped even trying to brush them away.

“Damn, look at this place,” the black dog chuckled. By now the dog was wolf-sized, like a beast from a fairy tale. Smoke poured from its nostrils and its panting jaws when it spoke. “You’ll never make Good Housekeeping now.”

“Oh, I don’t know about that,” Clay said softly. “Do they run a Halloween issue?”

Clay was woken from a nap by a knock on the front door, a sound that he had not heard in a very long time. He treaded lightly to the entrance, being careful not to disturb any of the piles of garbage in the same manner that one might be careful not to disturb a large, sleeping animal. Kathy was on the other side of the peephole. “Clay?” she asked, knocking again and more insistently. “Clay, I want to talk with you.”

Clay undid the bolt but not the chain and opened the door a crack. “How did you find me here?”

“Liz looked you up in your company’s directory. Gee, Clay, don’t you ever mow your lawn? It looks like a jungle out there.”

Clay barely even remembered that he had a lawn. “Oh yeah,” he said. “I haven’t been feeling good lately. What do you want?”

“Liz told me that you’re not doing well. I just wanted to talk with you. I’m not happy with how we left things, and I thought it’d be better if we spoke in person. Can I come in?”

“It’d be better if you didn’t.”

“Please, Clay, just let me in.”

“Let her in,” the black dog ordered coldly. Clay’s heart froze as he thought about Kathy seeing him in his degraded condition, but his fingers undid the chain.

Clay winced to see Kathy’s shock as she stepped over the threshold. She took a handkerchief from her purse and held it over her nose and mouth. “Oh. My. God. Liz told me that you’d been really depressed since we broke up and that you’d lost your job, but I—I had no idea things were this bad for you. This is like something from one of those TV shows. Why did you board up all the windows? And what are these drawings on the walls? Oh my God.” She began climbing the stairs to the second floor, tracing the patterns with her pink, glossy fingertip.

“No,” Clay said. “Not your god. Not your god at all. It was a dog who did this. You shouldn’t be here. I don’t think it’s safe.” He glanced nervously at the black dog. The animal was drooling.

“No, this clearly isn’t safe,” Kathy said, peering disdainfully at the piss jugs stacked by the bathroom. “This whole house might have to be condemned.”

“Condemned. That’s a good word for it.”

“Lock the door,” the black dog said.

Clay resisted this command with every bit of his willpower, but his willpower had long since wasted away to scraps. He turned the deadbolt and put the chain back on. Just then there was an enormous crash from upstairs, like an over-stuffed dumpster vomiting up its contents, followed closely by the sound of something large shambling about.

“What’s that?” Kathy asked. “Clay, is anyone else living here?”

“I’m not really sure,” Clay said. “I used to think it was just me and my dog, but lately I’ve been thinking that the garbage hoard itself might be alive. At night, I can hear it breathing through pop-bottle nostrils and plastic bag lungs. I try not to wake it up.”

A vast pile of decaying waste slithered into view at the top of the stairs. It was not merely sliding about due to gravity but moving with definite purpose, a hideous new life spontaneously generated from the unbounded wretchedness that Clay existed in. The beast roared wetly, spraying urine and morsels of spoiled food, and then it tumbled down the stairs and absorbed Kathy into its mass as it rolled over her. She had time to scream once before she was swallowed up. There was some thrashing and struggling from inside the pile, and one of Kathy’s hands burst free grasping feebly for a lifeline, her manicured nails brown and smeared with waste. Then the pile squeezed in on itself tightly like a heart beating, accompanied by a squeal and the sound of crushing bone, and all was still again. From that day forth, the house’s bouquet included the sickly-sweetish smell of rotting human flesh.

The black dog woofed happily, and rolled over for a belly rub.

Eventually the black dog swelled to occupy the entirety of Clay’s home. Clay burrowed into its side and nested there like a tick. His whole world was an expanse of hot, oily, abyss-colored fur that heaved gently with each breath the monster took.

The two lived as mutual parasites, with Clay sustaining himself by drinking his dog’s vile blood, and the dog sustaining itself by drinking its master’s despair. Clay’s consciousness atrophied until the only thoughts he could think were tick thoughts, dim and ugly and occupied wholly by an incessant need to suckle.

Then one day the black dog vanished.

Clay awoke naked and coated with filth in his septic ruin of a home, dazed and frightened by the sudden absence of the being that had dominated him for so long. Very little of his mind was left, but some intuition told him that he should go outside.

As he opened the door, exposing himself to blistering daylight and fresh air that scorched his throat, Clay became aware of an animalistic roar bubbling up from behind him and a sensation of motion at his legs, like he was standing at the center of a foul and slow-moving river. His hideous hoard poured out of his house in an undulating column, an enormous, baleful serpent made of rotten trash and excrement. It sloshed into the gutters, devouring the muck and imbuing it with its own hideous semblance of life.

Then came the dead swarm. Thousands of deceased insects spilled outside in a pestilential cloud, burrowing into the soil and flying through the air. The sickness in his home was spreading throughout the world to poison the whole of the animal kingdom.

The daylight turned crimson and inky blackness spread across the sun, leaving only a thin tendon of bloody red at the edge. Clay, now far beyond the warnings he’d received in elementary school, stared directly into the eclipse. He saw his own dog staring back at him from the sky, its eyes burning holes in the firmament like incoming meteors.

“I never knew your name,” Clay murmured.

“They call me Fenris,” said the wolf, in a voice as loud and terrible as atomic war. “I needed something soft to eat before I was strong enough to hunt.” One by one the stars went out as the wolf pulled them into its omnivorous maw. Clay sat down on his stoop as the darkness deepened, letting the trash and crawling death wash over him, and watched his black dog swallow the last of the light.

Max D. Stanton is an academic and writer of weird tales who lives in Philadelphia with his great hound Bear and his imperious cat Tristan. You can find his work in publications including World Unknown Review, Sanitarium Magazine, Disturbed Digest, Lovecraftiana [forthcoming] and the Under a Dark Sign and Candlesticks & Daggers anthologies.

DEATH CARRIAGE

By Matthew Penwell

When I arrived in Marywood, nightfall was approaching. Two streetlights with dying flames greeted me. I went down the main street, feeling tired, and needing a good night's rest. I looked for a house that suggested any sort of boarding, but found none. The houses are small, most one story, and have a particular “old” look about them. I have searched my mind for a better word to put on them and have failed to find one.

I passed a side road, going off to my left, and was about to go down it when I spotted a man emerging from his house, wrapping a coat about his shoulders.

“Hallo,” I said to the man, approaching him.

He looked up at me in fright, slightly flinching back, his eyes wide and mouth ajar. The man looked as if he had just seen a ghost. His cheeks quickly regained their color. His mouth twisted into a snare.

“What do you want? Why are you riding a horse about town after dark?”

“I'm sorry, sir,” I responded, feeling confused. “I'm passing through town, and I was looking for a place to board for the night.”

“Brick house, on the corner. Light should be on in window. They always have a vacancy.” The man's eyes shifted, he looked me up and down, and then gave my horse a good looking over. “Best be on my way.”

The man hurried away, down the street.

I found the house readily enough. A two-story, brick, with an overhang over the stoop. Just like the man said, a light was on in the left window. I dismounted my horse and looked for something to secure him to. I noticed a series of hooks fastened into the ground. I lead him closer to the house and tied one end of a rope about his neck, the other about the hook.

I tried the door handle and found it locked. Odd, I said to myself. In all my travels, I had never encountered the entrance to a boarding house to be locked—especially if they had a vacancy. I knocked as hard as I could. Perhaps the owner had fallen asleep, I thought. I waited; eventually, the door opened.

A man dressed in a nightgown answered. He had a thick mustache of orange and only a few wisps of hair remained on his head. He looked at me, his eyes slits, one hand fishing about in the chest pocket of his gown. He found his glasses and put them on. A candle cast a golden red hue on one side of his face.

“I met a man in town who said you had a vacancy?”

“Fifteen cent a night. Twenty, if you want breakfast in the morning.”

I paid the man at the door; he inspected the money as if he thought it to be fake. I had met two men in the small town, and they had both searched me over like I was from another world. My stomach was beginning to feel a little unsettled. The man moved away from the door, letting me pass by. He turned quickly about, closed the door, and locked it.

The living quarters were large. Several book shelves lined the wall to my right, while on my left, a doorway opened up. The man moved past me, towards the kitchen. A wood stove stood in the corner, piles of kindle and logs on either side. A long table with five seats sat in the direct middle of the room. I could make out a small staircase towards the back.

“Go up the stairs. First room on your right. Door is open. If you smoke, open the window. I don't want my house smelling like tobacco.”

I went to the stairs and looked up. Without a candle, I felt like I was about to walk into the darkness of death. I went up slowly, the steps creaking and bowing under my weight. On the landing, I saw that all the doors were open but one. I supposed this was the owner’s room. A painting of a woman in evening wear hung on the wall beside the door. I could barely see it in the moonlight, but I made out enough to see that the woman was young, black haired, and had a grim sort of smile.

“This one,” the man said, behind me. I hadn't heard him walk up the stairs. I rounded quickly, my hands balling into fists, ready for a fight. The man was pointing at the open door on my right. He handed me the candle holder. “There is a pail in the corner if you need to relieve yourself.”

I looked at the man. “Does this place not have an outhouse?'

“We do, but it's in your best health to not go outside after dark.”

“But why? Did something happen? The man I saw in the streets looked at me like he was seeing a ghost.”

I saw the same shift in the owner of the border's house that I had seen in the man's outside. It was an agitated look, one that suggested I shouldn't ask questions, or that I was asking too many questions. The man turned away, removed his glasses from his face, and stuck them back in his pocket. Even before the man uttered the words, I knew the conversation was over.

“Be off to bed. Shall I wake you in the morning?”

“I'll wake on my own. G'night.”

The man shuffled down the hall, opened the closed door, and disappeared within. I turned and went into my own room. Looking about, I noticed there was a bed and a two-drawer dresser with a small mirror attached for shaving. Nothing else. I went to the bed and sat atop it. The fresh smell of the blanket and pillow held no reminder that someone else had slept on it. I set the candle on the dresser and went about untying my shoes. I put them beside the bed, hoisted my feet up, and weaved myself under the cover. I blew the candle out.

In spite of my heavy lids, I couldn't fall asleep. I turned onto my side and looked out the window of the room. Through the curtains, a shaft of moonlight shone onto the floor. The world outside was quiet. Being a native of New York, I was used to the sound of horses and carriages at all hours of the night; the shouting of people as they stumbled home from the saloon. I determined that's what it was: it was too quiet. The longer I lay there, the more I thought about the man on th

e street. Everything about his demeanor suggested he wasn't expecting to meet another person walking about. The sight of myself had nearly frightened him to death.

The picture of the man's fear-stricken face stayed with me. It was there when I closed my eyes: the hollow eyes, the balding head with the wind moving about the last remaining strands of hair, the red beard. The man's face was with me when sleep came, washing over me in a wave of discomfort.

I awoke. The room was dark. The shaft of moonlight had moved away from my window with the rotation of the moon. With my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I could make out the shapes of the room. I threw the cover off me and made my way to the pail in the corner. No matter how hard I tried, my mind couldn't wrap itself around the concept. The man had said they had an outhouse, but insisted I didn't use it—insisted I didn't go outside. Had there been a murder recently? Is that why he didn't want me going outside? I undid the button on my trousers and relieved my bladder. When I finished, I went to the window and looked out. The streetlights had been extinguished during my slumber, leaving the town cloaked in black. I went back to the bed and sat on the edge, still looking out the window.

What time of night, I couldn't tell. I had seen a clock in the foyer upon entering, but decided not to entertain myself by going to check the time. Instead, I checked the drawer for a box of matches. I found one in the bottom drawer, next to a Bible. I took the matches and lit the candle. The hue of the light casted shadows across the room, flickering ghosts. I no longer felt tired. I felt as if I had slept for days. I had it in my mind that I would stay awake until sunbreak, and then continue my travel. I didn't need a meal. There was food on my horse that would sustain me. But I needed something to do in the meantime. I pulled out the bottom drawer, got the Bible, and thumbed through it, reading a passage here and there.

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002

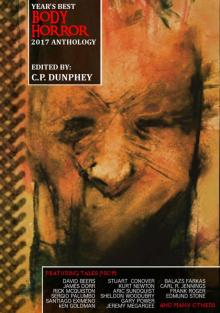

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002 Year's Best Body Horror 2017 Anthology

Year's Best Body Horror 2017 Anthology Hinnom Magazine Issue 003

Hinnom Magazine Issue 003