- Home

- C. P. Dunphey

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002 Page 6

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002 Read online

Page 6

I found the passage about Moses and decided to read the story in its entirety.

I read until I felt tired. My lids were once again heavy. Putting the old book on the nightstand, I blew out the candle, and lay there, listening to the silent air. From somewhere far away, I heard a cough that made my heartrate rise. Sleep was trying to wash over me. I kept dozing in and out. It was during this period that I heard the noise outside.

A carriage, the wooden wheels rolling over the cobblestoned road. I sat up in bed. Surely my mind is playing tricks on me. And looked at the window. A chill unlike anything I can describe trailed down my spine. My arms and legs rippled in gooseflesh. The room about me felt like it had dropped several degrees, but on the latter, I can't be sure. I reached for the candle and thought better of it. I didn't want the person thinking someone was prying on their privacy. So, I went to the window, pulled back the curtain an inch, and looked out into the dead street.

There were four of them. Not horses, but things that I will try my best to put into words. They were short, tanned skin, like old, worn out, baggy leather. Their ears came to a point below strands of oily hair. Their eyes were black and wide and glowed in the moonlight like onyx orbs. Two knife-like teeth protruded over their bottom lip. They were naked, save for a loincloth tied about their midsection. Each of the four things had a rope in their long-fingered hand, and hung over their back like a man carrying a heavy sack. They stepped in unison, their bare feet not making a sound. My eyes trailed from the things, up the rope, to the carriage. A man held the ropes in his hand, two in each. I couldn't make out much of his features, due to the black cloak he was wearing. But it looked as if he wore a hat under his hood, for it didn't go down his face but stuck out on either side. I noticed his hands. The moonlight made them look gray, like ash. He uttered something in a language that I do not have the faintest knowledge of. The things holding the rope hurried up their speed. The carriage had no roof, and I could see right inside it. A body lay inside, it's arms crossed over its chest, its eyes closed. I could see it was the body of a female by its long hair.

My mind tried to grasp at what I was seeing. The things pulling the carriage weren't human, I know that. My mind drifted off into fantasy. Being somewhat familiar with European folklore, a word came to mind. But I rejected the idea as soon as it came. Goblins were a thing of pure fantasy, made up, impossible to exist. But I had read stories about encounters with the small, squat men with large eyes and pointed ears. Dreaming. This isn't real. The carriage made a sudden right, disappearing into the forest line.

I stood at the window for a while longer, shaking, my body feeling like it had been dropped into a frozen pond. I let go of the curtain, letting it fall back into place. My legs felt like rubber. I reached out blindly, found the wall, and braced myself against it, trying to calm myself. Slowly, I made my way to my bed and sat on the edge. I sat there until sunrise. I don't believe I moved until I heard movement outside my door.

I sprang from the bed, ran to the door, and threw it wide. A woman let out a small scream and rounded on me.

“Who are you?” she demanded.

“I came here last night,” I told her, trying to keep my voice steady. “A man welcomed me in.”

The woman nodded. “Breakfast will be made shortly.”

“Ma'am,” I said, reaching out for the woman. She turned to face me. I shook my head. “Never mind.”

The woman looked at me oddly, turned, and went down the stairs.

I went back in my room and made the bed. Ten minutes later, I heard another pair of footsteps pass my room and go down the stairs. From below me, I heard voices: man, and woman. The woman said something I didn't make out, but I heard the man loud and clear: “No, I told him not to go outside.”

When I joined the couple, they were sitting at the table. A bowl of boiled eggs sat in the middle, next to a pan of cornbread. I pulled out five cents from my pocket and paid the man for the meal, sat down. The woman passed me a plate. I put a slab of cornbread and three boiled eggs on it.

“Sir,” I said, “what did I see last night? That's the reason you didn't want me to go outside.”

The man looked at his wife. She looked back, as if trying to communicate without speaking. I watched their faces. The woman's bottom lip trembled as she brought an egg to her mouth and took half of a bite. The man continued to look at his wife. He refused to make eye contact with me. Finally, he spoke:

“What did you see last night?”

The question shocked me. “Well, I don't know, exactly.”

“Best to keep it that way, then.”

“I saw a carriage,” I admitted, “it was being drawn by four men—only, they weren't men. And the carriage had a body in it, a female.”

“Bella Gein,” the woman said. “That's who you saw.”

“Who?”

“She was hanged last night for the murder of her husband,” the man said, gravely. “Believed in devilment, witchcraft, lived out in the woods. Thought she could get away with it.”

I nodded but didn't say another word. I no longer felt like eating. I said goodbye to the man and woman and thanked them for their courtesy. The man walked me to the door. We stood on the sidewalk together.

“Did they notice you?” the man asked me, his voice low.

“No.”

“It's best you leave now and don't talk about it with anyone.”

I untied my horse from the hook and straddled it. I started down the road, out of town. When I was a quarter mile away, I looked over my shoulder. The owner of the house had retreated inside. Turning my horse about, I headed towards the area where I thought I had seen the carriage vanish.

As I got closer, all the hair on my arms stood on end. My horse refused to go any farther. I dismounted him and tied him to a tree. I took a few steps into the leaf-covered ground, and looked about. There was no way a carriage could pass through here. The trees were too dense. I walked back out of the forest.

“What you doing?” a boy asked me, running to me, his eyes wide with panic, his feet kicking up dust. “Don't go back there. The caves are back there. That's where the devil lives.”

My heart jumped into my throat. I untied the horse as quickly as I could. My fingers felt numb as I picked at the knot. My mind made the calculations. I handed the boy a bill note as I mounted my horse. I had never wanted to get away from a place so much in my life.

Matthew Penwell was born in Florida, spent a majority of his life in a small town in Tennessee, and now currently resides in an even smaller town in Ohio. When he isn’t writing or working, Matthew spends most of his time practicing the guitar, listening to Black Metal, and reading. Influences include: Bradbury, Stine, and Faulkner. This is his first publication.

THE LITTLE DEAD THING

by John S. McFarland

Abel Edwin Jarre

128 Constantinople St.

St. Odile

Mr. George M. Nance

441 William St.

Pittsburgh

Nov. 16, 1922, Thursday

George:

If I can’t discover how to heal the wound God has put in my heart to know Him, to understand and satisfy my longing for Him and finally feel I am a part of His creation, I don’t know how I will face the years to come. I’m sorry to make these ravings (or musings) the main part of my letters lately, and perhaps that is why you have not answered me in so long, but I find I can hardly think about anything else.

You’ve heard this before, ever since Fismette. Before the war I never questioned that I knew the heart and will of God. I knew God kept me apart and disconnected from the world for some reason which would someday be apparent to me. So arrogant when you think about it, that any of us can understand the will of God! That day in Fismette when the Germans finally crossed the river and that boy, that German soldier of maybe twenty years of age who was carrying the flame thrower canister—remember when the bullet struck the tank and the lad went up in flames, remember how our b

oys cheered? It was a spectacle, an entertainment. We cheered and laughed as he, the enemy, screamed in the most horrific and pitiful agony. I aimed my rifle at his head to put an end to his suffering, but I hesitated. He was an enemy soldier, yes, but would not the act of shooting him in that way be something other than the accepted barbarity of war? I knew, as the Church says, I would have a murder on my hands, a mercy killing. This boy who may have been raised a Catholic as I was, who only thought he was doing his duty to his country, must die slowly and painfully so that I may not have a mortal sin on my soul. Lieutenant Allen shot him, mercifully, so his immolation only lasted a few seconds.

I killed two men that day, two I know of. Acceptably as a protocol of battle. I shot them on the bridge and they fell into the river. It didn’t affect me any more than putting my boots on that morning. They were strangers, objects, targets, the enemy. But that night I could only think of the burned boy who died in such a different way. I wondered how is the suffering and loss of an enemy, the other, different from ours? Of course, it isn’t. An obvious enough proposition, but I didn’t really understand it before then. But the war was full of moments like that wasn’t it? As we said on the ship home that night when our time in the 111th was nearly over: War is moments where familiar things became understood in a different way, or understood more deeply. It’s that connection that must be made to this world, to all of life which I have been seeking and turning over in my head for four years. I’m sorry to refer to it so often. One day I hope to put it out of my mind.

With your wife’s serious illness maybe you have had these pointless ‘metaphysical’ thoughts too? I am glad Mae is feeling better (per your last letter in March), and her consumption was relieved by your trip to Arizona. Perhaps you will move there? I would hope to see you again and to meet her on your way west, if you do. I wish we had been able to do that on your first trip, but there it is.

I write to Eustace Kirby too as you may remember. He was as near as the landing at DeCastres Island in my very town in June, according to the visitor list in the newspaper, and he didn’t visit me. “Eustace Kirby of Bremen Ridge, Pennsylvania who served with distinction in the 111th Pennsylvania in the recent war, travelling to San Francisco, California with his wife Kate. The Kirbys came by boat down the Ohio then up the Mississippi to catch the train in Ste. Odile and travel north to their connection in St. Louis to continue their journey.” I have written him seven or eight times since getting reestablished here in Ste. Odile. He was a few blocks away and chose not to visit me. I am at a loss to understand this.

I mentioned in my last letter also that my hopes of a future with my Lucy were fading. Her father has never approved of me. She says he wants no veteran of the war for her husband. He suspects that no man who lived through it would be unaffected enough to make a suitable mate for his daughter. He would never thrust such a man to be capable of a normal family life after all we experienced. I have asked her for a final answer, asked that she consider only her own feelings, not her family’s. I am still waiting to hear from her.

My work continues at the assay laboratory at Osage Lead Company. Mr. Karl, my supervisor has hired a new technician; Roualt is his name. He is supposed to be my assistant, and I am to train him to process samples. The young man is concerned with details and organization and is good enough at arithmetic, so he is learning quickly, as I expected he would. It seemed to me there were barely enough samples to keep me occupied, as our production has fallen off so drastically since the war, but Karl has insisted that we will be much busier in the future, that there are prosperous times ahead, and we must be prepared. He has said there will soon be a push to add lead to gasoline, as it makes automobile engines run smoother, and our production will soon increase. But, I was unconvinced by this assertion and I asked Karl if he is dissatisfied with my work, or has come to dislike me for some reason, but he says I am imagining it. He says I spend too much time imagining plots against myself. I don’t know what it is, George, but the town has not accepted me, since I returned from the army. Treves has noticed it too, noticed that he is ostracized now. In his case his injuries have changed his appearance so terribly; perhaps that is what is behind his situation. His surgery has fallen off to nothing. But as far as I can tell, I am unchanged, outwardly at least. But Ste. Odile has changed toward me. I am an outsider here.

Though I still harbor some concern for him, even Treves seems alien to me. What are the chances that two fellows from a tiny village on the Mississippi should find themselves at the outbreak of a great war, in the same unit in a Pennsylvania battalion? I would have taken no bet on it! You would think with that great coincidence and the unifying experience of what came after, we would be brothers or fast friends thereafter, but we hardly have two words to say to each other. There it is.

I will close now so I do not miss the mailman.

Your Friend,

Abel

Later

November 17, Friday

George:

I dozed off and missed sending yesterday’s letter. Much has happened today. My suspicions were correct. Karl dismissed me this morning. He said my work had suffered recently, which I know is not true. He said Roualt can replace me very well now and at a lower rate of pay. And Karl is hiring a friend of Roualt’s to be his assistant at an even lower rate. There it is! Dismissed! A veteran rewarded for his service. I had few personal things to retrieve, collected my $7.00 in wages and walked the several blocks home to Constantinople Street.

It turned much colder overnight and the wind whipped in from the river as I made my way home. I have saved $42.00 which might sustain me for a few weeks but as I walked against that cold wind I knew I must find other employment quickly, and that this new development will damage my prospects with Lucy even further unless I succeed. As I approached my front gate I saw the ancient Mrs. Zell, my landlady, on the front walk. With some obvious revulsion, she was examining something on the ground near the porch stairs. She looked up and saw me and waved urgently for me to hurry to her.

“I’ll swan I’ve never seen such an ugly thing!” she said. She seemed awestruck and unwilling to take her eyes off the thing on the ground.

“What is it?” I could just see part of it behind a boxwood bush.

“I never seen such a thing. It’s some ugly little thing, some little dead thing.” Mrs. Zell’s manner of speaking is to emphasize at least one word in every phrase or sentence. “What is that? I wonder how long it’s been there? I never noticed it until just now.”

“It looks like it’s been dead a while,” I said. “Maybe the cat dragged it here?” That prospect seemed unlikely. The creature was not as large as a cat but looked formidable. It was unlike anything I had ever seen. It was hairless except for a few patches of a gray, coarse fur near its hindquarters and on its feet . . . its six feet. It had forepaws armed with long, curved talons and two sets of hind legs, similarly armed. There was a short set of hind legs in front of a longer, more powerful set. The short legs seemed to be vestigial or perhaps some sort of malformation, because like the forelimbs of the great Tyrannosaurs found in the West lately, they seemed to have no practical use.

The head of the creature was beyond classification. It had a short, muzzle-less face, two bulging eyes, filmy and gray in death, and a round mouth much like a lamprey’s with many needle-like teeth. Below the weak jaw were two appendages tipped with bony barbs, that reminded me of the stinger of a scorpion. Its skin was gray with a bluish tinge, sagging and wrinkled and showing the first stages of decay.

“It’s a chimera,” I said. “I’ve never seen such a collection of deformities. What is it? We had many monstrous specimens in jars at the university, but nothing like this. Doesn’t have much of a smell, does it?”

“I can’t touch it,” Mrs. Zell moaned. “Please get rid of it for me, Mr. Jarre.”

“I wonder if we should notify someone? Some county official or the sheriff, or even one of my old professors at the Carthesian University?”

/>

“I don’t want to see it again. Just dispose of it immediately, please, and . . . why are you home from work in the middle of the morning?”

You may remember my interest in natural history and zoology. It was I who always cared for the war horses when I had the chance and looked after cats and dogs displaced by battle. In school, I loved zoology more than chemistry, my major field of study, but couldn’t foresee a way to make a living at it. I could not see myself dumping this horrific and unique creature in a grave, or disposing of it in the city dump. I assured Mrs. Zell I would dispose of the dead thing.

I went up to my room and found an old lidded laboratory jar with a two-gallon volume I had retrieved from the lab after Karl threw it out. I had a supply of denatured alcohol, too, which I had brought home for cleaning and as lamp fuel. I poured about a gallon of this into the jar. In the shed back near the alley, I found a burlap sack and a shovel. From just outside the kitchen window I could hear Mrs. Zell speaking to her niece on the telephone, telling her the story of the discovery.

I slid the shovel under the body of the creature and lifted gently. It was so fragile with putrefaction that the gray skin tore as I lifted, revealing a swarming and disgusting mass of maggots inside. My gorge rose and I thought I might eject my breakfast on the spot! It seemed odd to me that with the weather turning colder the maggots would still be active in the body, but I soon saw a wisp of steam rise from the torn skin as though the body were still warm inside. As I held the top of the sack open and passed the laden shovel under it, one of the barbs on the creature’s jaw scraped below my left thumb. I gently lay the burden inside the sack and immediately started to notice that the punctured place on my hand was going numb. By the time I lifted the sack off the ground, my left hand had gone completely dead and had become nearly useless. I reckoned the barbs deliver some sort of anesthetic or paralytic agent, as some insects and spiders do, which may aid in the killing of its prey.

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002

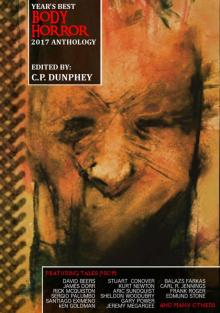

Hinnom Magazine Issue 002 Year's Best Body Horror 2017 Anthology

Year's Best Body Horror 2017 Anthology Hinnom Magazine Issue 003

Hinnom Magazine Issue 003